By NYAFF

Welcome back to UNCAGED, the official podcast of the New York Asian Film Festival where we delve into the world of Asian cinema and explore inspiring stories behind films and the artists who create them. I’m your host Amanda Cattel.

In this exclusive episode, we delve into the recent Chinese film, "The Shadowless Tower," released in China in October of last year and in select US theaters starting on March 15.

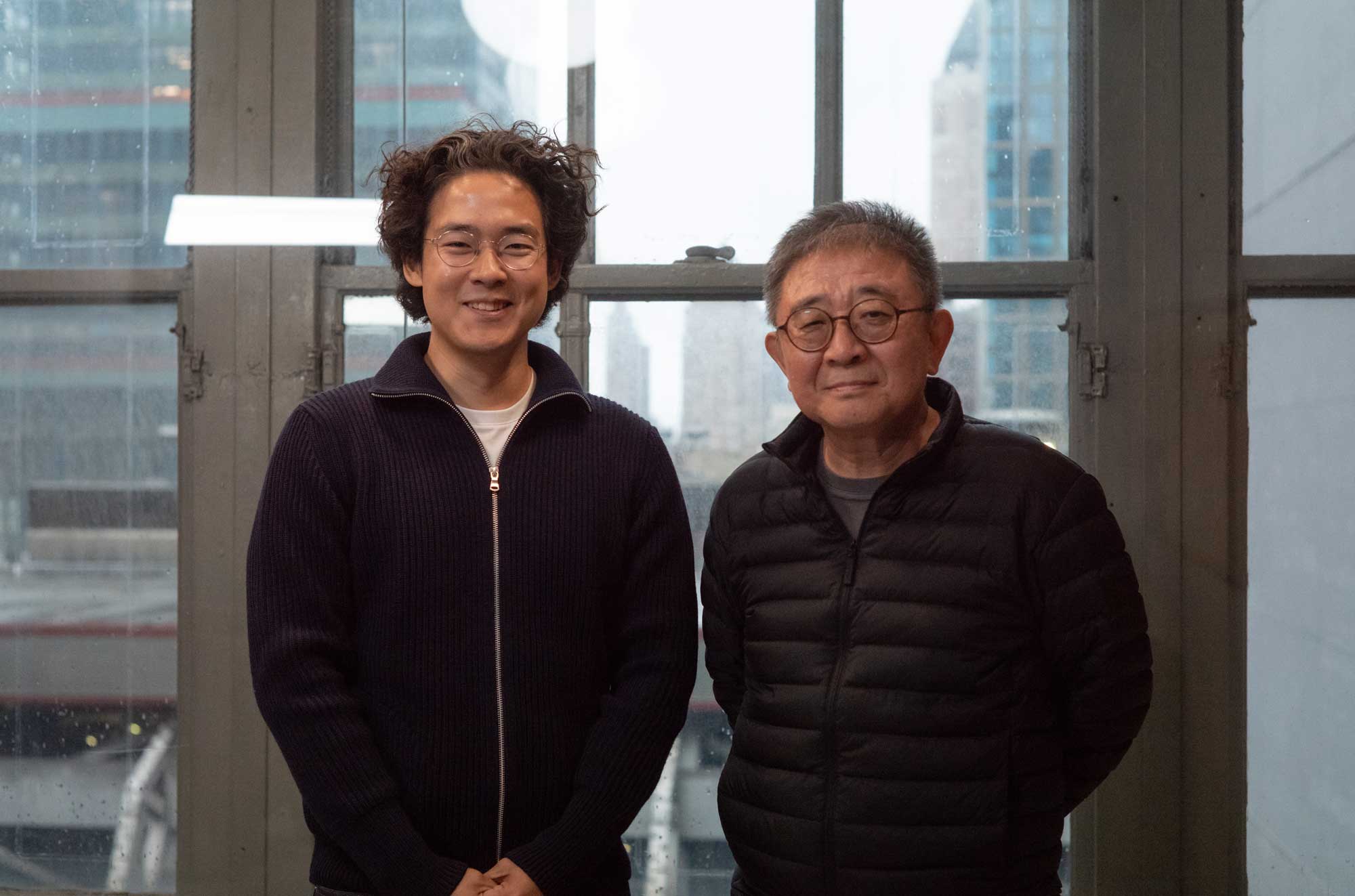

Director Zhang Lu sits down with Peter Yoon to delve into the film's creation. Yoon, a Ph.D. candidate in NYU’s Department of East Asian Studies, brings expertise in Korean diasporas and their narratives. We are thrilled to showcase Lu's insights in this episode.

The "Shadowless Tower" is a study in unease and tension in family relations, as well as emotional transactions in general, with Beijing serving not only as its backdrop but as a cornerstone of the story.

While arthouse Korean-Chinese filmmaker Zhang Lu typically illustrates the experiences of outsiders, the director was actually inspired to highlight stories of Beijing locals due to his personal desire to film in the Chinese capital, as well as his childhood memories that took place in this specific environment. The professor-turned-film director wrote the screenplay while quarantined in a hotel in Guangzhou in the latter part of 2020.

On Soundcloud

On YouTube

Director Zhang Lu, known for his arthouse films focused on the disenfranchised, returns with "The Shadowless Tower," a meditative portrait on the compromises and unexpected beauties of growing old.

In this film, director Zhang intricately weaves the complex relationship of the Xin Baiqing as Gu Wentong, a divorced middle-aged writer who has abandoned poetry for the mundane work of food criticism. Gu's well-worn routine is upended by an encounter with young photographer Ouyang Wenhui (played by Huang Yao), whose influence prompts him to re-evaluate his past and present.

Compelled by Zhang's nuanced exploration of these complex themes, Peter Yoon, a Ph.D. candidate at NYU's Department of East Asian Studies and a longtime admirer of the director's work, joined him for an insightful conversation about the creation of this compelling film.

This podcast interview was conducted in Korean.

Transcribed interview:

Peter Yoon (PY): Welcome, Director Lu.

Zhang Lu (ZL): Yes, thank you.

PY: The first question I have for you is about your latest film, The Shadowless Tower. I’m curious about the White Tower itself. When did you first encounter the tower and how did it become the subject of your film?

ZL: I lived in Beijing for some thirty or so years. The White Tower, which is actually a Buddhist temple, is located to the west of Beijing’s center. Generally speaking, you could say that the tower is at the center of Beijing. When I was younger, I often hung out in that area (laughter). Drank a lot, too. So I’ve come to know the area around the tower very well since many of my friends are from that neighborhood and I visit them there. There are a lot of traditional-style buildings and architecture that are still well-preserved and occupied by local residents. Those buildings are built neatly, in a square shape and gray color; sometimes, in dark red, like crimson, which used to indicate class difference. The crimson color used to be the color of the emperor. So, there are crimson and gray, which dominate this part of Beijing’s architectural urbanscape, and then there is the white of the tower that suddenly appears out of the crimson and gray. In many ways, the white does not quite fit in. The tower is also rounded, which stands out from the neat squares of that part of Beijing’s urbanscape and the routinized lives of its residents. After having lived there for a while, I started to feel a sense of consolation every time I saw it. I became curious about this feeling, which served as a starting point for this film.

PY: Yes, now that you say it, I understand what you mean by this sense of consolation, which seems to be the quiet undercurrent of the film. But this film takes place in a major city, the capital of China no less. Your previous films take place in smaller and relatively “minor” cities, like Fukuoka, Gyeongju, and Gunsan, so I’m curious about the impetus behind that shift if there were any, this shift from “minor” to a “major” city.

ZL: You’re right, it is a large city, with a population of about 20 million. I couldn’t possibly have shot a film about Beijing as a whole. But it is a city that I’ve lived in for over thirty years and this particular neighborhood (Xicheng District), for me, is also a space that embodies my feelings and the flow of my emotions. So I chose that spot and shot the film in and around that neighborhood, with the tower as the center.

I was also curious about how people are living in Beijing today. Around the White Tower, the buildings have almost remained the same over the years. But the sentiments or the attitude of the people…they change over time depending on their age at the time they were living there, right? But even then, there is a very subtle difference in the rhythm of the people who live in the old Xicheng District and that of those who live in the newer, more developed parts of Beijing. I wanted to capture that subtle difference in rhythm as well.

PY: Yes, your films are very attuned to those subtleties as you said, especially to various temporalities that co-exist in an urban space. There is also another location in the film, Beidaihe, which is a seaside village and serves almost as a contradistinction to Beijing. How did you come upon that place?

ZL: Beidaihe is located 300km to the east of Beijing. It’s a popular holiday spot for a lot of Beijing residents. In the film, it’s also where we find the father of the protagonist, who originally lived in Beijing but because of a misunderstanding some time in the 70s, self-exiles himself to Beidaihe. Although he has lived there for a while, all of his sentiments or emotions, they dwell in Beijing. This contrast or spatial difference of emotions, of living in one place while feeling as though one is in another place, was very interesting to me. Especially today, I think a lot of people live and feel this way, or at least can relate to this being in one place while their feelings are in another place because of how memory mediates their attachment (or lack thereof) to one place over the other. Across the world, many people seem to embody this condition.

PY: The shadow of the White Tower, as it is also mentioned in the film, is said to be in Tibet. In that sense, the tower symbolizes various motifs in the film, some of which are constancy and change, stability and displacement, intimacy and distance.

Relatedly, I want to ask more about the relationship between the two characters, Gu Wentong and Ouyang Wenhui. I found their relationship interesting because it’s very complex and hard to define. Gu Wentong is a middle-age man and Wenhui is a young woman in her twenties but they have a much more complex relationship than simply a romantic one. Certain types of loss or absences seem to bring them together, and their relationship is quietly dynamic, as they dance over the romantic territory at one point but also fall into a play of father-daughter roles that allow them to fill in for one another. Could you elaborate further on their relationship? This is a repeating theme throughout your other films as well. Why are these kinds of non-conventional, if not ambivalent, relationships important, or worth exploring, for you?

ZL: In reality, when you look into your emotions, it’s very rare that you can pinpoint a certain emotion. By nature, emotions are ambiguous. You can’t speak about them with absolute certainty, much less define them with clarity or conclusiveness. However, by force of habit, we, especially filmmakers, tend to come to conclusions about our emotions. For instance, a beautiful or painful love. It’s rarely that way in reality. When it comes to filmmaking, I’m not so interested in finding clarity. I’m more interested in things that are unclear, that we come close to knowing but never quite so. When you look around, reality is much more like that most of the time; it’s just that we pretend not to see these ambiguities. So, I point the camera towards those ambiguous emotions, their relations, and distances. When you point the camera and look into them, you find that all the joy and sadness that we experience in rhythm are steeped in ambiguities like fog. In that fog, you can encounter many different kinds of what we perceive as the same thing. Rather than compartmentalizing our emotions, it’s important to enter that fog of ambiguities with courage and assess them in such a condition.

PY: That’s really important. Lately, our world is becoming increasingly chaotic, and the more things become confusing, the more people seek clarity or certainty—politically, socially, and culturally. People find it difficult to accept and face chaos, which is leading to more violence.

Perhaps for this reason, I really liked the protagonist, Gu Wentong. Like a plant or a tree, he has a kind of resilience that allows him to endure hardships—although his over-politeness obscures that quality. While he has a quiet resilience to make it through that fog, as you mentioned earlier, Gu Wentong’s character also seems to have a touch of middle-class melancholia. There is one scene in which he is at a dinner gathering with his friends, and they all break into singing the Beijing Olympic theme song and later share their divorce stories. It seems like his issues from the past are in many ways paradoxically wound up with his middle-class status. So, he has this plant-like resilience while also suffering from middle-class melancholia. I was wondering if you could speak more on that.

ZL: Most people live their lives through work. When they’re young, they spend a lot of time with their friends and colleagues. But once they graduate high school and college, they enter the workforce and eventually grow distant from those friends they’d spent their youth with. This is the case for most people in China and Korea—I’m not sure how it is here (in the US).

PY: Yes, it’s quite similar.

ZL: When they do get together at a small gathering of friends or a reunion, they are able to see the changes in each other’s sentiments and attitudes. There is a sense of absent time and space in their relationships. Especially in the movie, these friends are middle-aged. They’re mostly sad and, in the film, they share this sadness over drinks. Sadness is the default condition of a middle-aged person.

Depending on what kind of job they have, what kind of social life and experiences they have after their youth, a person’s rhythm changes, however subtly. If you look at Gu Wentong’s friends, they’re all living quite actively—many of them, if not all, have been divorced and remarried, it takes courage to remarry (laughter). If his friends are moving forward, Gu Wentong is someone who dwells in his body. His sense of rhythm and attitude is really contrasted with those of his friends. While his friends are moving on with their lives, Gu is a little behind and dwells like a plant or a tree as you said. Strangely, my attention goes to characters like Gu. Those who move forward or make progress, they’re all similar. But if someone dwells in their body, they dwell in and with time and memory. If you explore the emotions of those who are “left behind” because they dwell in their bodies like plants, you are able to articulate what precious things our time has lost or forgotten. In these kinds of characters, you are able to find “old” temporalities that are commensurate with ours. But if you look into those people who “chase” time [in the name of progress, for instance], you can’t really see these things.

PY: That sense of dwelling and the kind of temporality that emanates out of such an attitude is an apt description for your films. You tend to portray cities and the various layers of memories and temporalities they embody. In that sense, this film and Gu Wentong’s character in particular seem to be no exception. And there is a sense of hope in Gu Wentong’s character. It’s not a triumphant kind of hope… I keep thinking of plants when speaking about Gu Wentong.

(Laughter)

ZL: Plants do make frequent appearances in the film.

PY: Yes, exactly. A lot of scenes that show care for plants. Perhaps that’s why.

The next question is a related one. A lot of the characters, in their relationship to each other and to strangers, too…they begin to mimic one another and start to grow alike. For instance, there’s a woman on the bus who is massaging her ears, then Gu Wentong begins to massage his, too. There’s also a man walking backwards that he runs into and mimics or echoes later in the film. This left a deep impression on me because it’s a form of affirmation, as shadows and reflections are to us, and there’s a lot of such faint but affirmative mimicking, parallels, and reflections across relationships in the film. It’s rarely verbalized or confirmed by the other person but it’s more gestural, which somehow both parties understand and feel. Not to mention, there are a lot of scenes of the characters’ reflections in a mirror and other surfaces, showcasing the phenomena of light similar to shadows. Is this kind of empathic or intuitive connection also reflected in your filmmaking and writing process—for instance, when working with actors and actresses?

ZL: One could say that one of the most basic human instincts is to mimic. If one were not to mimic another, their relationship would grow distant and even arrogant. If you observe someone in their infancy or developmental stages, they mature by mimicking, whether consciously or unconsciously. When you grow older, say in your forties or fifties, your father’s friends tell you that you’re a lot like him (laughter). Without knowing, you have always already been mimicking someone, whether your father or someone else. In that sense, mimicking is really invaluable. If you’re not mimicking, it means that you don’t have any curiosities about yourself or others. You lose your innocence or naïveté. In other words, you lose that most beautiful part of yourself.

But in the case of someone like Gu Wentong who dwells in time like a plant as I said earlier, they preserve their child-like instinct. Most people would consider such a person to be strange. In reality, however, this child-like desire to mimic is the most precious thing. I don’t know if you remember but earlier in the film (The Shadowless Tower), Gu Wentong can be seen wearing traditional shoes that are black with white soles; but later, after he sees Wenhui wearing Converse while sharing a coffee with her near the White Tower, he is seen wearing the same ones as hers, which she points out to him. Even though he is middle-aged, Gu has a curious attitude, which in fact has little to do with his age.

How much one has preserved their innocence or naïveté, or how much they have lost it—I’m interested in the relationship between these two.

PY: Yes, his character is fascinating for that reason. His past selves—from youth, teenage years, his early manhood, and middle-aged life—seem to coexist in his body and expressions.

My last question is about the man that Gu Wentong talks with toward the end of the film when he goes to visit his ex-wife at her hospital. The man—her new husband or boyfriend, it isn’t clear—tells Gu that he is a Korean language instructor. When Gu Wentong asks him to say a word in Korean, he utters the Korean word for “love” (사랑), which happens to sound like the Uighur word for “fool”. I also heard “apology” in that word (Laughter). What is love for you? Foolishness? Apology? What do they mean in the context of your films?

ZL: Whenever we talk about our emotions, especially about love, we tend to compartmentalize them as we talked about earlier. So these terms take on strict, limited meanings.

For me, because I’m a third-generation Korean, “sarang” has a certain meaning for me. But nowadays, a lot of K-dramas have made their way into China and have become popular, so many people know the word and what it means. In the Uighur language, there is a word that sounds exactly the same as the Korean word. So that made me think about how these different languages exist in one another, about what it would be like if I were to mix the different meanings of these words—or, on the other hand, keep them separate. There are many homonyms or similar-sounding words across languages. It’s as though despite the efforts to compartmentalize the meanings over time, these different languages and their words come, by chance, to fill the gap in their counterparts.