By Dylan Foley

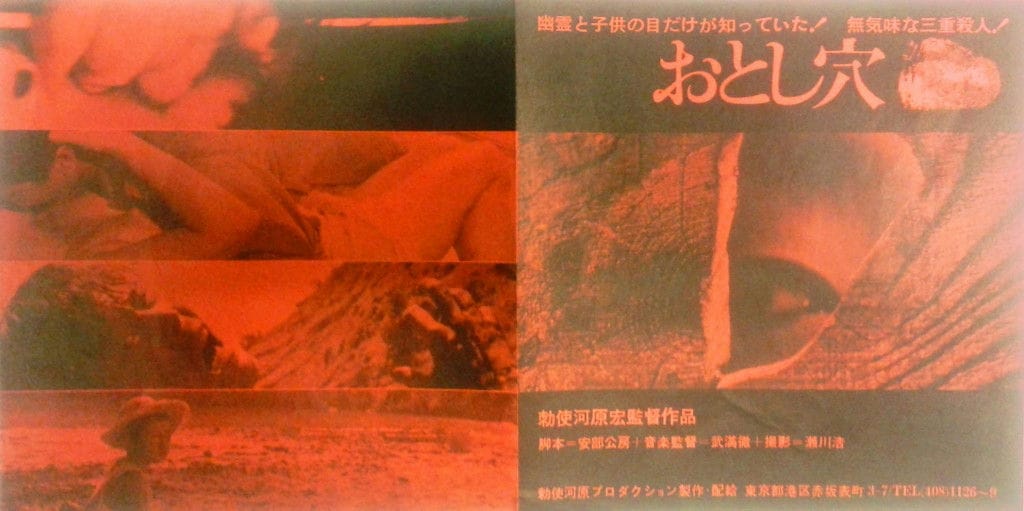

Engulfed by the oppressive heat of a deserted mining town in Kyushu, a miner (Hisashi Igawa) and his son stumble into a malicious web of fate, mired in the clutches of a mysterious man in white with nameless origins and inexplicable motives. Directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara ("Woman in the Dunes") in 1962, "Pitfall"(Otoshiana) is a landmark work in Japanese film for a multitude of reasons, the foremost being that it marked the first collaboration between Teshigahara and novelist Kobo Abe, whose writing Teshigahara also adapted for his next three narrative features. Equally as important to this momentous creative marriage is that "Pitfall" was the first Japanese film to be distributed by the Art Theatre Guild (ATG), the independent distribution and production company that helped ignite the Japanese New Wave’s radical experiment with cinematic format.

After daydreaming about being reincarnated as a union worker, the miner is assassinated by the white-clad grim reaper. His ghost is then forced to witness the assassin execute a diabolical union-busting blackmail scheme. By using the miner’s corpse to frame his doppelganger, the man in white stokes the flames of two warring unions’ petty grievances against each other, fast-tracking their implosion. Teshigahara’s painterly sense of composition is trained here on the barren landscapes of industrial society, registering the verdant hillsides that have been substituted with craggy stone faces and piles of coal and dirt, crumbling under the feet of the father and son who traverse it in search of fair wages.

Roland Domenig, who curated an ATG retrospective at Vienna Film Festival in 2003, describes the company’s role in the “Nuberu Bagu” as something which can “hardly be exaggerated,” writing in his book, "Art Theatre Guild: Unabhängiges Japanisches Kino 1962 - 1984," “in the 1960s and 1970s the Art Theatre Guild held all the strings as far as Japanese independent cinema was concerned. They united the directors of the Nouvelle Vague who had left the studios, the documentarists of Iwanami Productions, directors of sexploitation movies as well as important representatives of amateur and experimental film.”

This surge of artistic rebellion followed the second golden age of Japanese cinema in the 1950s, when the cinephilia of the general public in Japan was at a fever pitch, with 1.13 billion people going to the movies in 1958 and 547 films produced domestically in 1960. To meet the immense demand for new films, studios like Shochiku seized the opportunity to capitalize on the kind of subversive cinema that was forging a new path across the globe with movements such as the French Nouvelle Vague and Brazil’s Cinema Novo.

Hence, some enterprising executives decided to throw their hat in the ring and manufacture the same in their own country, elevating a nascent group of assistant directors to helm their own first full-length features, including Nagisa Oshima, Masahiro Shinoda, and Yoshishige (aka Kijū) Yoshida, in an initiative which came to be known as the “Shochiku Nouvelle Vague.”

Conversely, due to the artificial beginnings of the movement, Oshima and Yoshida soon disavowed their association with it, eventually defecting to ATG in their search for less commercially-minded partners. T

his, along with the later additions of pioneering auteurs including Susumu Hani ("Nanami: The Inferno of First Love"), pink film director Koji Wakamatsu ("Ecstasy of Angels"), and avant-garde directors Shuji Terayama ("Throw Away Your Books," "Rally In the Streets") and Toshio Matsumoto ("Funeral Parade of Roses"), cemented ATG’s status as an outfit more equipped to meet the needs of an artistic rebellion. Though the impetus of the New Wave is usually credited to Shochiku’s fortuitous promotions, a look at Teshigahara’s position as a leader in communal arts spaces attests to the vibrance of a pre-existing alternative avant-garde that was gestating in discursive arenas prior to any studio involvement.

The heir to a preeminent ikebana (flower arrangement) school founded by his father, Teshigahara was involved with a number of other grassroots arts organizations that functioned as incubators for the avant-garde community, such as the leftist arts and culture magazine Seiki no Kai (“The Century Society”), the avant-garde artist collective Jikken Kob

o (“Experimental Workshop”), and the international arthouse film club Cinema 57. In this way, Teshigahara was a bridge between the ATG and the avant-garde, most importantly through the Sogetsu Art Center (SAC), where he served as director from its founding in 1958 until its closure in 1971.

Described by art critic Yoshiaki Tono as the “epicenter of the avant-garde,” SAC served as a venue for the curation and exhibition of a sprawling variety of arts and performances at the vanguards of their respective mediums. In her book on Teshigahara’s borderless conception and practice of the arts, _The Delicate Thread_, art critic Dore Ashton details his programming at SAC, screening imported films from the likes of Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, and Jack Smith, putting on experimental jazz and dance performances, and plays by Terayama, Juro Kara, as well as the famous French enfant terrible Jean Genet.

SAC also hosted artists ranging from John Cage and Yoko Ono to Nam June Paik and Robert Rauschenberger, who at one point famously destroyed a specially made kinkyobu, or gold-leafed folding screen, in front of the entire organization. These events underline Teshigahara’s chameleonic tendencies. He initially studied painting in college but later wore any hat he could get his hands on, including sculpture, pottery, flower arrangement, calligraphy, opera, and film.

Teshigahara’s use of archival footage showing the drastic working conditions of miners at the time is an early example of New Wave directors’ penchant to straddle the line between documentary and fiction. He liked to call this the “fantasy-documentary” style, saying, “in the art of being a director there should be no difference between making a documentary and making a fiction film.” This quote evokes a deep well of quasi-documentary films, a technique which imbricates fiction and reality together and would later reappear in ATG films such as Shohei Imamura’s A Man Vanishes (1967) and Funeral Parade of Roses.

Though much to his displeasure, Oshima is often referred to as the “Japanese Godard,” but perhaps this tension between fiction and documentary which Teshigahara sought makes him a more fitting comparison to Godard’s ideas of generating friction between sound and image. In his collaborations with composer Toru Takemitsu, Teshigahara demonstrated a similar push-and-pull, created by jarring, discontinuous musical notes. As Ashton writes, “Without fail, Takemitsu supplied the kind of counterpart that Teshigahara needed, the ‘collision’ of sound and image that Teshigahara sought.”

"Pitfall’s" connection to a cinematic lineage of disenfranchised children culminates in the abandoned miner’s son who, in the wake of violence, is left to experience life as a voyeur through peepholes and removed vantage points. One need look no further than Vittorio de Sica’s "The Bicycle Thieves" (1948) for an antecedent, but Luis Buñuel’s "Los Olvidado"s (1950) and Francois Truffaut’s "The 400 Blows" (1959) also served as references for Teshigahara’s version of criminalized youth in the post-war era, a genre already known as taiyozoku in Japan, epitomized by Nakahira Kō’s Crazed Fruit (1958).

Ashton talks about the period in Teshigahara’s life when he was filming "Pitfall," saying, “'Pitfall' was, in a way, a manifesto for himself affirming the importance of the documentary style that—as he had been quick to observe in Buñuel—could be put into the service of a subjective expression of political and social situations.” Where Barbara Kopple’s "Harlan County," USA (1976) illuminated the plight of coal miners through a strike in Kentucky, Teshigahara’s tale of a boy orphaned as a consequence of an omniscient evil’s meddling in the miner’s unions was an apt fictional vehicle for one of Teshigahara and Abe’s recurring thematic preoccupations: divided identity under bureaucratic hierarchies.

The late designer Issey Miyake described Teshigahara as “curiosity itself.” Indeed, he embodied that spirit in both his personal and professional lives: as an organizer championing the exhibition of a variety of artforms, and as an artist seeking to challenge conventions and push the barriers of his medium. Despite being his first feature, "Pitfall" was a full-fledged realization of that motto.

Today the ATG distribution and exhibition model seems an outlandish fantasy. The company had the full use of 10 different theaters to give each of their films a month-long theatrical run, regardless of box office numbers or attendance. This included the legendary Shinjuku Bunka and Theatre Scorpio (Sasori-za), which became high-profile venues for experimental film screenings and underground theater performances along with Sogetsu.

Despite the company having its own studio ties (its main funder was Toho), ATG was unquestionably in the artist’s corner, exemplifying the possibilities of independent studio offshoots when they have resources to leverage. In that sense, ATG stands as a platonic ideal in the history of theatrical exhibition and curation as a company which prioritized support for filmmakers and creative freedom over the commercial considerations inherent in film production.