By Ning Chang on December 26, 2023

December opens with a stark overhead shot of a schoolgirl murdered on a riverbank, her blood a bright red smudge against the almost monochromatic stillness. The shock of violence stains the start of the film, and it stains the cast of characters struggling to move on seven years after: the victim’s now-divorced parents Katsu (Shogen) and Sumiko (Megumi), and her murderer, Kana (Ryo Matsuura), whose resentencing hearing brings them together again.

December, Anshul Chauhan’s third feature in Japanese, is ostensibly a courtroom film; it tackles the thorny issue of juvenile detention in Japan as Kana’s headline-seeking lawyer strives to reduce or commute the harsh sentence she received as a juvenile. However, Chauhan expands the film beyond the court to create a multilayered picture of the lives affected by tragedy, who wrestle with notions of justice, revenge, and reconciliation as the case goes back on the docket.

For Chauhan, the film’s crux is obsession over the past and the intense reactions that it can dredge up. While the script had sat on his desk for a while, a puzzle waiting to be figured out, his breakthrough came with the realization that he could sideline the legal focus and instead discuss the individual toll of continuing to seek justice years after the gavel falls.

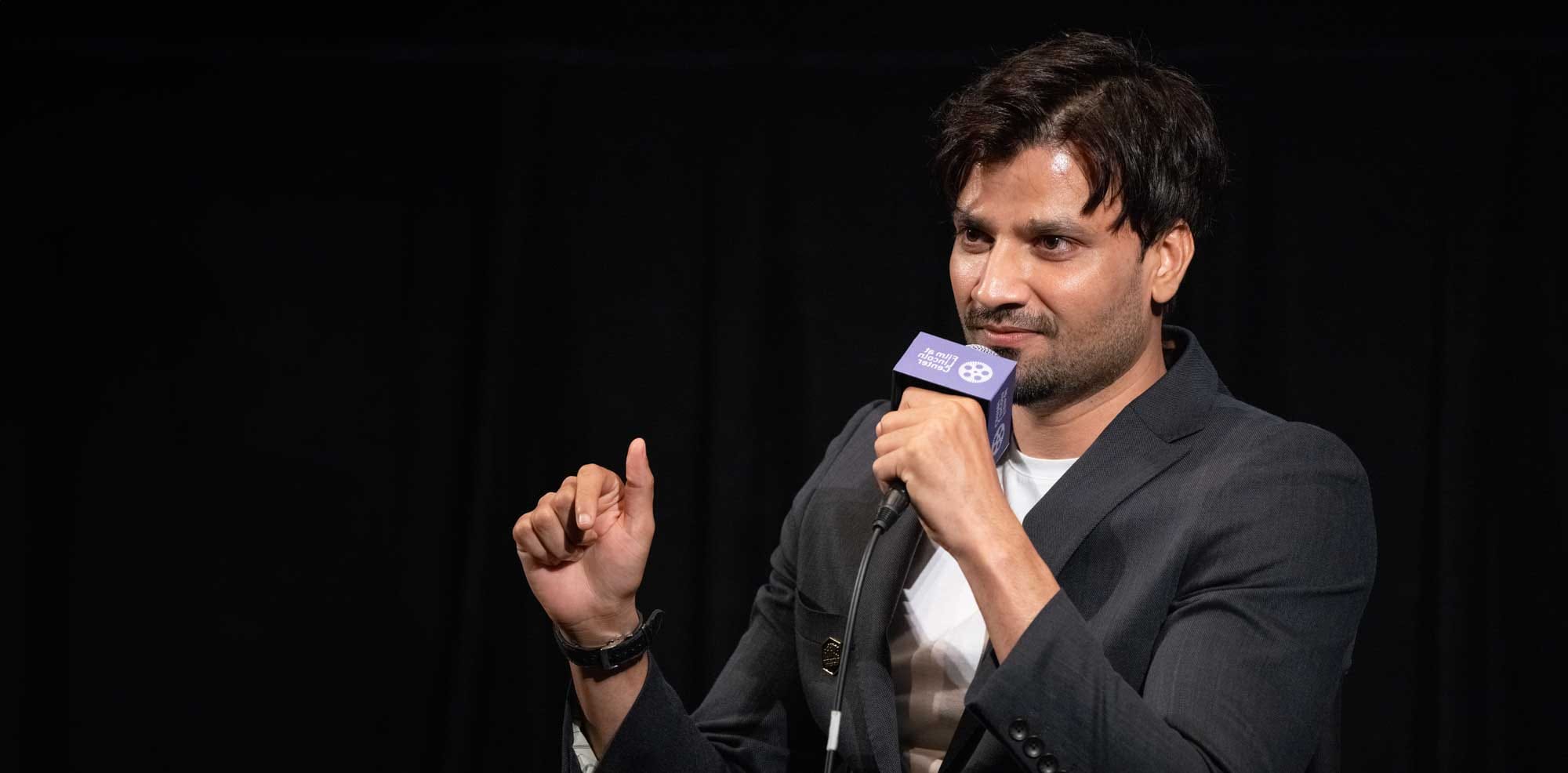

“I was thinking that it had to be a legal drama, so it might be boring or too small of a scale for me to get a budget for,” he explained. “Then, I pulled myself out and just focused on, okay, I should look at it as a human drama, because there's also a life outside court.”

The brisk court procedure is almost a sideshow; the meat of the film is in the time spent following the personal lives of the characters. Chauhan’s steady camerawork and liberal use of quick jump cuts catch the cast of characters in a fractured present as they slide from scene to scene. The characters reflect on seemingly immovable life paths against the backdrop of a manicured and choreographed visual world. There is a dollhouse nature to their settings and actions that make the film feel slightly surreal—it’s a storytelling choice that highlights the internal struggles of the characters as they begin to understand that justice isn’t necessarily revenge, but more so a process of facing uncomfortable, challenging truths in the hopes of reaching a sense of forgiveness.

Drawing from his own experiences, Chauhan admits that much of the process of making the film was about understanding forgiveness in his own life. “It’s not that simple,” he says. “I'm talking about forgiveness (in this film) because I'm not able to forgive certain things.”

Chauhan found himself relating heavily to Kana, who faces continued anguish over her actions in the past but also grapples with the conviction that her hand was forced in many ways by the circumstances she found herself in. “It was the bullying part which drew me because it's a very sensitive subject for me personally. As a kid, I was in [a] military academy, and I faced a lot of bullying for many years,” he explained. “When I was a kid, I used to always think, I want to kill this guy. But if I had actually done it, what would have happened?”

The story itself has a kernel of truth: in fact, it was inspired by several real-life, high-profile cases of teenagers convicted of murder who faced long sentences in Japan’s notoriously opaque and severe court system.

Human Rights Watch has described Japan as having a “hostage justice system,” where people arrested are denied bail and the right to remain silent. In 2020, they found that Japan’s pretrial detention system caused those accused of a crime to be detained for months and even years. Once defendants arrive at trial, they face a staggering 99.8% conviction rate.

For juveniles in particular, the Japanese justice system has also struggled to react to a moral panic of the 1990s, where crime coverage was dominated by the figures of kireru kodomo, or “snapped kids,” whose impulsive and unexplained cruelty was blamed on an inherent, incurable darkness. From 2000 until today, there have been multiple reforms to the juvenile justice codes, which increasingly treat justice-involved teenagers as adults. In 2018, the criminal age of majority in Japan was lowered to 18, and even juveniles under 17 can be prosecuted as adults for a large variety of “severe” crimes.

Kana is portrayed on the surface as the classic kireru kodomo, whose lawyer’s plea for resentencing and nuanced notion of remorse are treated as abnormal by the system. Matsuura’s performance is measured, but the stillness of her face betrays a shifting intensity as the audience begins to tease out the truth of her motivations. Her stoniness hides a darkness, but one that we learn comes from a society willing to believe in and act on inherent ideas of good and bad.

Dealing with such a sensitive subject without sensationalizing it was a challenge for Chauhan and his lead actor, Shogen. Chauhan cites a documentary he watched, Neil Rawles’ Japanese Teen Killers, as an important reference for how to grapple with the emotions in December, especially in the creation of the character of Katsu.

“In that documentary, there's a father who every day drives to the school and parks outside,,” Chauhan says. “He stares at the road and looks at the kids when they're leaving the school. And he always looks for this kid who killed his kid. Even though he doesn't do anything—he just looks at him—he might do something.”

This kind of silent and watchful anger, where something might just bleed through, is evident in Chauhan’s love affair with Shogen’s cologne-model appearance, dedicating dozens of shots to capturing the moment in close-up when his reserved nature morphs into something uncontrolled.

“I created this emotion from nothing because I don't have kids,” Shogen says. “But now my wife is pregnant, and expecting a daughter in October. Now it's different; it's very different. If it happened to me in real life, it's more complicated.”

Shogen describes Katsu as “ordered by revenge,” forever willing to dredge up the past in an effort to try to return to when his family was whole. Yet, in many ways, he too is trapped by his quest for vengeance. Kana’s lawyer, pressing Katsu during his testimony in court, points out that Katsu calls himself a writer, yet he hasn’t published anything in the seven years since his daughter died. His single-mindedness and his grief also led him to lose his wife, as Sumiko, wrapped up in tailored shades of wintry gray, reminds him. Yet she also feels inexorably drawn back to the past out of a sense of long-buried guilt.

“Parents who have lost their kids, they accuse themselves,” Shogen says. “They, out of most people, accuse themselves, or they accuse each other.” If anything, the courtroom bent of the film is meant to excavate where the characters feel blame should lie. More often than not, blame circles back to fall on the characters themselves for failing to see each other as human.

In two key scenes, where Sumiko and Katsu seek out Kana outside of the courtroom and on their own terms, this realization becomes exceedingly clear. With the line between victim and aggressor increasingly blurred, Katsu and Sumiko make the choice to leave what happened in the past, but even for a relatively clear-cut decision, Chauhan chooses unsettlement over a fully satisfying ending. Forgiveness, for Chauhan, is a continuously reoccurring choice, one where you can choose differently day by day. It has no easy answers.

“We didn't mention if he really forgives her or not,” Shogen says, “but obviously, my character has changed a bit. Something is changing his mind.”

Chauhan agreed, adding, “I could have shown [Kana], you know, smiling, or [Katsu] hugging her, but the feeling of what's happening next was important for me to have the audience to bring back home. He might do something; you never know.”